The sales enablement industry has taken tremendous strides in recent years, but by most measures, it's still a relatively immature function. While there’s a talented and growing body of practitioners that are doing sterling work to advance the industry and sales performance, for the most part, there’s a distinct lack of standardised sales enablement best practices, planning models and frameworks. This can, must and will change.

To fill this "best practices void" and play my part in elevating the role of sales enablement I often take ideas from other fields and apply them to my work at HubSpot. In my mind we shouldn’t be afraid to re-use what has worked before - indeed I often and unashamedly adapt or build upon a successful idea or parts of one. A good idea is a good idea after all.

One concept that intrigued me and has the potential to be applied to sales is that of weak-link and strong-link thinking. The idea was popularised in The Numbers Game: Why Everything You Know About Soccer Is Wrong, a book written by Chris Anderson and David Sally. The basic premise is that you can adopt one of two approaches - you either help your weakest players (weak-link thinking) to improve or you focus on making your star players (strong-link thinking) even better.

Ultimately, both schools of thought seek the same outcome (improve performance), but the approaches are wildly different. However, conventional wisdom, in most cases advocates a strong-link approach. The reasons for this are straightforward and understandable - it’s often more sexy, more glamourous and in many cases, feels like the right thing to do. Indeed, it's human nature to want to be associated with the top performers and winners. But that doesn't mean it's the best course of action.

While the book hones in on sport, weak-link and strong-link thinking can be applied to any situation where there’s a broad distribution of performance and by proxy, talent. To me, a sales organisation seemed like an ideal environment to test out this idea. Modern sales organisations, especially within the software as a service (SaaS) industry are extremely data driven - unlike sport, it’s easy to objectively quantify who the best and worst performers are.

I also want to make it absolutely clear that I don’t think there’s a definitive right or wrong answer when it comes to a weak or strong-link approach. Each business and context is unique, after all. However, in a SaaS business, especially one that works to a monthly sales quota, speed is incredibly important. By improving sales rep performance this month, instead of next, you will have a material impact on revenue. The key is to evaluate whether a weak-link or strong-link approach will have the bigger impact, and then how quickly it can be achieved.

Strong-link thinking

Strong-link thinkers, as the name suggests want to start at the very top and help the star performers to get even better. By improving the strongest players, clearly you will improve the overall performance of the team. People use basketball as an example of a strong-link sport - there’s many chances in a match and just five players on a court, so you want to give the star player the ball as much as possible. Strong-link sports are heavily reliant on their top talent.

From a sales point of view, the idea of making a top sales rep even better is a noble one, however it can be a greater challenge than people appreciate. Once somebody is a top performer, it’s unclear just how much more they can improve by (if at all). If a sales rep always averages 200% of quota attainment, is it possible to better that? Improvement is not infinite - there’s an upper ceiling and in seeking out further gains you may unwittingly pass the point of diminishing returns and waste time and effort.

Importantly, there’s often few existing playbooks and structures to enable top performers to get better. It’s unchartered territory and typically requires additional resources to get right. That's not necessarily a bad thing, but it needs to be taken into account. On the upside, top performers are easy to identify - it’ll be there in the daily sales waterfall for all to see. The question is less about whether sales reps have the ability to further improve, it’s more about is it possible.

Weak-link thinking

By taking a weak-link approach you start at the bottom - you focus on and seek to improve the poorest performers. By improving the weakest players and bringing them up to average you significantly improve the overall performance of the team.

Football (soccer) is often cited as a weak-link sport - there’s few chances, a relatively high number of players on the pitch (11) and many are typically involved in a goal. In this type of scenario you want the average ability of your football players to be high and evenly distributed. It’s unglamourous and goes against conventional wisdom, but how weak your weakest players are matters in football. It’s less about the stars and more about the mediocre journeymen.

From a sales perspective, weak-link thinking is effective as there’s clear and quantifiable room for improvement. There’s also likely to be existing playbooks and structures in place, which can be repurposed or adapted, rather than created from scratch. In theory, this means a weak-link approach should require less resource.

I’m an advocate of weak-link sales enablement as it’s easy to identify under-performers, but the more important question to consider is whether they can improve. Does the sales rep (or reps) have it within them to get better? Secondly, and it’s important to recognise, it’s probable a group of underperforming sales reps will have a higher attrition rate than other cohorts - they may be interviewing elsewhere or on a performance improvement plan (PIP). In short, you may be investing time in people that cannot improve or don’t intend to stick around. As long as the sales reps have the aptitude and enthusiasm to improve, a weak-link approach can yield lots of low-hanging fruit.

Improving Sales Performance with a Weak-Link Approach

How HubSpot adopted a weak-link approach and improved sales rep quota attainment by 31%

As an individual contributor (IC) I’m constantly thinking about where I can invest (I use that word very deliberately) my time to have the biggest impact in the shortest period. It’s for that reason I created a sales enablement programme that adopted a weak-link approach.

Once I studied the data it was crystal clear that a weak-link approach was the most direct route to improve the overall performance of the sales organisation. And to shed some light on my role, the key goal I’m tasked with hitting each month is to ensure the sales organisation as a whole reaches a certain percentage of quota attainment. While there’s certainly an element of, “What gets measured, gets done”, I think, “A rising tide lifts all boats” is the more accurate aphorism.

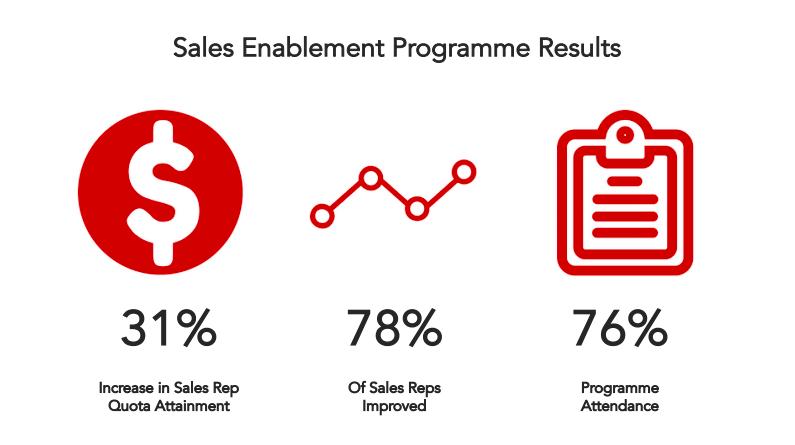

But let’s talk about results. That’s what matters. Unfortunately, there’s some data from the programme that I can’t reveal. However, what I can say is, 78% of sales reps that participated in the programme improved, and average quota attainment of the group increased by 31%. These two numbers are important and show that the programme worked, but what’s more valuable and what I can share is how we achieved these results.

Why we ran the programme

At the beginning of 2017 HubSpot made a bunch of significant changes to our go-to-market (GTM) strategy - these impacted everything from our sales motion to compensation structure to product line. In short, we made some big, transformational bets and made them quickly (as always).

As our quarter drew to a close, our topline numbers were strong, however there were some sales reps not hitting quota. Having taken a deep dive on the quarterly sales figures I identified a cohort of sales reps averaging less than 95% quota attainment over the course of the quarter. This is when I first heard about weak-link and strong-link thinking. Indeed, it got me thinking about how I could accelerate their path to 100%+ quota attainment. The business rationale for supporting this cohort was strong - as a company HubSpot has aggressive growth plans and to ensure we realise them, we need sales reps to be hitting quota quickly and then consistently. It's as simple as that.

Guiding principles

The programme was designed to be agile, scrappy and different. Based on discussions with sales reps we created a set of principles to codify the essence of the programme. This would provide clarity for both participants and subject matter experts, who delivered the training.

You can see the principles below:

I want to acknowledge that the programme was heavily tailored to the needs of the group, so scaling and replicating the programme is a challenge. But I’m okay with that - I’d much rather run a programme that is effective and tailored to the needs of sales reps, but lacks scalability, versus one that scales well, but is poorly suited to the needs of the sales reps. In truth, I was also keen to simply test if this new weak-link approach, focussed on poor performers would work - we could tackle scale afterwards.

More generally, I'm an advocate of creating principles as it clearly shows what something is - and of equal importance, what it isn’t. This reduces ambiguity and grey areas, and helps show how we’re trying to innovate and improve. I shared these principles with the subject matter experts two weeks ahead of their session, so they understood what we wanted to achieve.

Positioning

Having worked with sales reps across a wide range of industries for over a decade now, it’s clear there’s only two types of sales rep. The one that is hitting quota and the one that is not. Confidence, momentum and trust are tough to create and easy to damage, so for that reason we wanted to be extremely empathetic about how we communicated and positioned the programme. This wasn’t a pre-PIP move - it was quite the opposite. The sales enablement programme represented a big investment, but we believed that with additional support this weak-link cohort of sales reps would be able to hit 100% of quota attainment.

Results

The programme was ran over an eight week period and achieved the following results:

In addition, the average NPS for the subject matter experts was 67 and for each session it was 63. I fully recognise that measuring the impact of training is difficult, so we ran an A/B test. One group took part and another did not. Interestingly, but perhaps not unsurprisingly, the group of sales reps not invited to the programme on average only increased quota attainment by 9%.

Learnings

The was no secret hack, tactic or ingredient that led to the success of this programme. We went back to basics, spoke with sales reps to understand what they wanted from training and then delivered a programme based on what sales reps told us, plus what data and sales managers showed they needed. Most importantly, sales reps engaged with the programme - I believe the way we positioned and communicated the programme was essential, but ultimately, the sales reps deserve the credit.

Taking a step back, I’m not surprised by the improvement. Being purposeful about learning and setting aside time each week to learn is how you improve. We see a lot of potential in the programme - not just the increase in quota attainment, but the high NPS, so we’re doubling down and rolling it out globally at HubSpot.

I also think we selected the right cohort of sales reps - supporting sales reps that are underperforming and helping them become better is an efficient use of resources. There’s always going to be existing resources and playbooks in place to help them improve. The caveat is, whether or not the sales reps have the ability and motivation to improve. Although, if they don’t, I would argue it’s more a recruitment or sales manager challenge, than a sales enablement one.

While this post highlights the success of a weak-link programme we ran at HubSpot (and continue to), it’s important to state that we also run initiatives for our top performers. As is often the case, things are rarely clear cut, and black or white, and a blended, adaptable approach is what we’ve found works best. However, what I do hope this post does is challenge conventional wisdom and offer a fresh perspective on what is a perennial sales enablement challenge. It’s easy to overlook your weakest sales reps, but that doesn’t mean you should. Helping them improve can be the quickest way to increase overall performance of the sales organisation, and that's what really matters.